Difference between revisions of "Sikh history"

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

===Sri Guru Angad Dev ji=== | ===Sri Guru Angad Dev ji=== | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Sikhhistory.jpg|thumb|300px|Satguru Nanak]] |

{{Main|Sri Guru Angad Dev ji}} | {{Main|Sri Guru Angad Dev ji}} | ||

In 1538, Guru Nanak chose [[Lehna]], his disciple, as a successor to the Guruship rather than one of his sons.<ref name=Shackle_2005/> Bhai Lehna was named [[Guru Angad]] and became the successor of Guru Nanak. He married [[Mata Khivi]] in January 1520 and had two sons, (Dasu and Datu), and two daughters (Amro and Anokhi). The whole Pheru family had to leave their ancestral village because of the ransacking by the [[Mughal Empire|Mughal]] and Baloch military who had come with Emperor [[Babur]]. After this the family settled at the village of [[Khadur Sahib]] by the [[River Beas]], near [[Tarn Taran Sahib|Tarn Taran]] Sahib, a small town about 25 km. from [[Amritsar]] city. | In 1538, Guru Nanak chose [[Lehna]], his disciple, as a successor to the Guruship rather than one of his sons.<ref name=Shackle_2005/> Bhai Lehna was named [[Guru Angad]] and became the successor of Guru Nanak. He married [[Mata Khivi]] in January 1520 and had two sons, (Dasu and Datu), and two daughters (Amro and Anokhi). The whole Pheru family had to leave their ancestral village because of the ransacking by the [[Mughal Empire|Mughal]] and Baloch military who had come with Emperor [[Babur]]. After this the family settled at the village of [[Khadur Sahib]] by the [[River Beas]], near [[Tarn Taran Sahib|Tarn Taran]] Sahib, a small town about 25 km. from [[Amritsar]] city. | ||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

His devotion and service ([[Selfless service|Sewa]]) to Guru Nanak and his holy mission was so great that he was instated as the Second Nanak on 7 September 1539 by Guru Nanak. Earlier Guru Nanak tested him in various ways and found an embodiment of obedience and service in him. He spent six or seven years in the service of Guru Nanak at Kartarpur. | His devotion and service ([[Selfless service|Sewa]]) to Guru Nanak and his holy mission was so great that he was instated as the Second Nanak on 7 September 1539 by Guru Nanak. Earlier Guru Nanak tested him in various ways and found an embodiment of obedience and service in him. He spent six or seven years in the service of Guru Nanak at Kartarpur. | ||

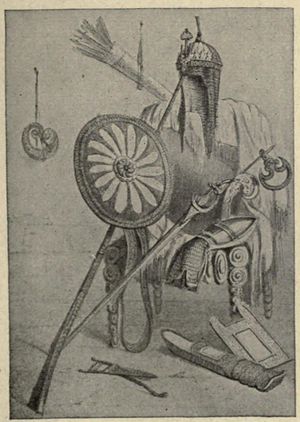

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Sikhhistory1.jpg|thumb|300px|[[Sri Guru Angad Dev ji|Bhai lehna]] serving [[Satguru Nanak]]]] |

After the death of Guru Nanak on 22 September 1539, Sri Guru Angad Dev ji left Kartarpur for the village of Khadur Sahib (near Goindwal Sahib). He carried forward the principles of Guru Nanak both in letter and spirit. Yogis and Saints of different sects visited him and held detailed discussions about Sikhism with him. | After the death of Guru Nanak on 22 September 1539, Sri Guru Angad Dev ji left Kartarpur for the village of Khadur Sahib (near Goindwal Sahib). He carried forward the principles of Guru Nanak both in letter and spirit. Yogis and Saints of different sects visited him and held detailed discussions about Sikhism with him. | ||

Sri Guru Angad Dev ji introduced a new alphabet known as [[Gurmukhi]] Script, modifying the old Punjabi script's characters. Soon, this script became very popular and started to be used by the people in general. He took great interest in the education of children by opening many schools for their instruction and thus increased the number of literate people. For the youth he started the tradition of Mall Akhara, where physical as well as spiritual exercises were held. He collected the facts about Guru Nanak's life from [[Bhai Bala]] and wrote the first biography of Guru Nanak. He also wrote 63 [[Salok]]s (stanzas), which are included in the [[SGGS ji]]. He popularised and expanded the institution of ''Guru ka Langar'' that had been started by Guru Nanak. | Sri Guru Angad Dev ji introduced a new alphabet known as [[Gurmukhi]] Script, modifying the old Punjabi script's characters. Soon, this script became very popular and started to be used by the people in general. He took great interest in the education of children by opening many schools for their instruction and thus increased the number of literate people. For the youth he started the tradition of Mall Akhara, where physical as well as spiritual exercises were held. He collected the facts about Guru Nanak's life from [[Bhai Bala]] and wrote the first biography of Guru Nanak. He also wrote 63 [[Salok]]s (stanzas), which are included in the [[SGGS ji]]. He popularised and expanded the institution of ''Guru ka Langar'' that had been started by Guru Nanak. | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Sikhhistory2.jpg|thumb|300px|[[Sri Guru Angad Dev ji]]]] |

Sri Guru Angad Dev ji travelled widely and visited all important religious places and centres established by Guru Nanak for the preaching of Sikhism. He also established hundreds of new Centres of Sikhism (Sikh religious Institutions) and thus strengthened the base of Sikhism. The period of his Guruship was the most crucial one. The Sikh community had moved from having a founder to a succession of Gurus and the infrastructure of Sikh society was strengthened and crystallized – from being an infant, Sikhism had moved to being a young child and ready to face the dangers that were around. During this phase, Sikhism established its own separate spiritual path. | Sri Guru Angad Dev ji travelled widely and visited all important religious places and centres established by Guru Nanak for the preaching of Sikhism. He also established hundreds of new Centres of Sikhism (Sikh religious Institutions) and thus strengthened the base of Sikhism. The period of his Guruship was the most crucial one. The Sikh community had moved from having a founder to a succession of Gurus and the infrastructure of Sikh society was strengthened and crystallized – from being an infant, Sikhism had moved to being a young child and ready to face the dangers that were around. During this phase, Sikhism established its own separate spiritual path. | ||

Revision as of 14:10, 4 December 2019

| Gurmat - Beyond Heavens Mindstate |

|---|

|

Satguru Nanak once he became embodied with God and totally reformed spiritual, social, community practice throughout the world starting with the Punjab region, then the rest of Bharat, then Tibet, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, then Middle East Europe, Africa and America in the reign of early modern history. Satguru Nanaks's religious practices was formalized by Satguru Guru Gobind Singh on 30 March 1699 by Gobind Singh baptizing five persons from different social backgrounds to create the Khalsa. The first five, Pure Ones then baptized Gobind Singh into the Khalsa fold. They became the ideal of social, moral, political, ideals in practice for the benifit of all beget of any desire.

With Guru Arjan Dev Ji's Martydom Sri Guru Haregobind sahib ji Sikhism militarized to oppose Mughal hegemony and elevate their status from 'lowly religious aesthetics'.[1] to give them a more prominent play in politics and raj as well.

After Guru Tegh Bahadur's martyrdom Sikhs faced heavy percussion by the Mughal and Afghani forces more of this is outline in detail below.

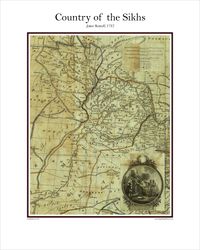

During the early 19th century Mahajarah Ranjeet Singh came into rule unifying the Sikh rule of various misls. His raj extended to Peshawaar, Sindh, Tibet, Down to doaba border where the British Raj had taken over India. Ranjit Singh's raj was the most powerful and most wealthiest of the world at the time. He was also the first leader to play seculaism at play to that large of an extent. The people adored his honest rule and benovuount chartactistics. Even the enemies admired him as once they were subdued they would still get a jagir to control over.

The partition of India in 1947 saw heavy conflict in the Punjab between Sikh and Muslims, which saw the effective religious migration of Punjabi Sikhs and Hindus from West Punjab which mirrored a similar religious migration of Punjabi Muslims in East Punjab.

Contents

- 1 Early Modern (1469 CE – 1750 CE)

- 2 Age of Revolution (1750 CE – 1914 CE)

- 2.1 Nawab Kapur Singh

- 2.1.1 Extensive Looting of the Mughal Government

- 2.1.2 Government Sides with The Khalsa

- 2.1.3 Dal Khalsa

- 2.1.4 5 Sikh Misls of the Dal Khalsa

- 2.1.5 Preparing Jassa Singh Ahluwalia for leadership

- 2.1.6 State Oppression

- 2.1.7 Sikhs attack Nader Shah

- 2.1.8 Sikhs kill Massa Rangar

- 2.1.9 Sikhs loot Abdus Samad Khan

- 2.1.10 Mughals increase persecution

- 2.1.11 The Khalsa strengthen military developments

- 2.2 Jassa Singh Ahluwalia

- 2.2.1 Chhota Ghalughara (The Lesser Massacre)

- 2.2.2 Reclaiming Amritsar

- 2.2.3 Reorganization of the Misls

- 2.2.4 Khalsa side with the Government

- 2.2.5 Harmandir Sahib demolished in 1757

- 2.2.6 The Khalsa gain territory

- 2.2.7 Wadda Ghalughara (The Great Massacre)

- 2.2.8 Harmandir Sahib blown up in 1762

- 2.2.9 Sikhs retake Lahore

- 2.2.10 Peace in Amritsar

- 2.3 Jassa Singh Ramgarhia

- 2.4 Sikh Empire

- 2.5 Punjab under British Raj

- 2.1 Nawab Kapur Singh

- 3 Contemporary Period (1914 – present)

- 4 See also

- 5 Notes

- 6 References

- 7 External links

Early Modern (1469 CE – 1750 CE)

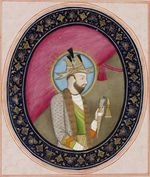

Satguru Nanak

Satguru Nanak (1469–1538), founder of Sikhism, was born to Kalu Mehta and Mata Tripta, in a Hindu family in the village of Talwandi, now called Nankana Sahib, near Lahore.[2] His father, a Hindu named Mehta Kalu, was a Patwari, an accountant of land revenue in the government. Nanak's mother was Mata Tripta, and he had one older sister, Bibi Nanki.

From an early age Guru Nanak seemed to have acquired a questioning and enquiring mind and refused as a child to wear the ritualistic "sacred" thread called a Janeu and instead said that he would wear the true name of God in his heart as protection, as the thread which could be broken, be soiled, burnt or lost could not offer any security at all. From early childhood, Bibi Nanki saw in her brother the Light of God but she did not reveal this secret to anyone. She is known as the first disciple of Guru Nanak.

Even as a boy, Nanak was fascinated by hindu religion, and his desire to explore the mysteries of life eventually led him to leave home. It was during this period that Nanak was said to have met Kabir (1440–1518), a saint revered by many. Nanak married Sulakhni, daughter of Moolchand Chona, a trader from Batala, and they had two sons, Sri Chand and Lakshmi Das.

His brother-in-law, Jai Ram, the husband of his sister Nanki, obtained a job for him in Sultanpur as the manager of the government granary. One morning, when he was twenty-eight, Guru Nanak Dev went as usual down to the river to bathe and meditate. It was said that he was gone for three days. When he reappeared, it is said he was "filled with the spirit of God". His first words after his re-emergence were: "there is no Hindu, there is no Muslim". With this secular principle he began his missionary work.[3] He made four distinct major journeys, in the four different directions, which are called Udasis, spanning many thousands of kilometres, preaching the message of God.[2]

Guru Nanak spent the final years of his life in Kartarpur where Langar (free blessed food) was available. The food would be partaken of by Hindus, rich, poor, high or/and so called low castes. Guru Nanak worked in the fields and earned his livelihood. After appointing Bhai Lehna as the new Sikh Guru, on 22 September 1539, aged 70, Guru Nanak met with his demise.

Sri Guru Angad Dev ji

In 1538, Guru Nanak chose Lehna, his disciple, as a successor to the Guruship rather than one of his sons.[3] Bhai Lehna was named Guru Angad and became the successor of Guru Nanak. He married Mata Khivi in January 1520 and had two sons, (Dasu and Datu), and two daughters (Amro and Anokhi). The whole Pheru family had to leave their ancestral village because of the ransacking by the Mughal and Baloch military who had come with Emperor Babur. After this the family settled at the village of Khadur Sahib by the River Beas, near Tarn Taran Sahib, a small town about 25 km. from Amritsar city.

One day, Bhai Lehna heard the recitation of a hymn of Guru Nanak from Bhai Jodha (a Sikh of Guru Nanak Sahib) who was in Khadur Sahib. He was thrilled and decided to proceed to Kartarpur to have an audience (darshan) with Guru Nanak. So while on the annual pilgrimage to Jwalamukhi Temple, Bhai Lehna left his journey to visit Kartarpur and see Baba Nanak. His very first meeting with Guru Nanak completely transformed him. He renounced the worship of the Hindu Goddess, dedicated himself to the service of Guru Nanak and so became his disciple, (his Sikh), and began to live in Kartarpur.

His devotion and service (Sewa) to Guru Nanak and his holy mission was so great that he was instated as the Second Nanak on 7 September 1539 by Guru Nanak. Earlier Guru Nanak tested him in various ways and found an embodiment of obedience and service in him. He spent six or seven years in the service of Guru Nanak at Kartarpur.

After the death of Guru Nanak on 22 September 1539, Sri Guru Angad Dev ji left Kartarpur for the village of Khadur Sahib (near Goindwal Sahib). He carried forward the principles of Guru Nanak both in letter and spirit. Yogis and Saints of different sects visited him and held detailed discussions about Sikhism with him.

Sri Guru Angad Dev ji introduced a new alphabet known as Gurmukhi Script, modifying the old Punjabi script's characters. Soon, this script became very popular and started to be used by the people in general. He took great interest in the education of children by opening many schools for their instruction and thus increased the number of literate people. For the youth he started the tradition of Mall Akhara, where physical as well as spiritual exercises were held. He collected the facts about Guru Nanak's life from Bhai Bala and wrote the first biography of Guru Nanak. He also wrote 63 Saloks (stanzas), which are included in the SGGS ji. He popularised and expanded the institution of Guru ka Langar that had been started by Guru Nanak.

Sri Guru Angad Dev ji travelled widely and visited all important religious places and centres established by Guru Nanak for the preaching of Sikhism. He also established hundreds of new Centres of Sikhism (Sikh religious Institutions) and thus strengthened the base of Sikhism. The period of his Guruship was the most crucial one. The Sikh community had moved from having a founder to a succession of Gurus and the infrastructure of Sikh society was strengthened and crystallized – from being an infant, Sikhism had moved to being a young child and ready to face the dangers that were around. During this phase, Sikhism established its own separate spiritual path.

Sri Guru Angad Dev ji, following the example set by Guru Nanak, appointed Sri Amar Das as his successor (the Third Nanak) before his death. He presented all the holy scripts, including those he received from Guru Nanak, to Guru Amar Das. He breathed his last breath on 29 March 1552 at the age of forty-eight. It is said that he started to build a new town, at Goindwal near Khadur Sahib and Guru Amar Das Sahib was appointed to supervise its construction. It is also said that Humayun, when defeated by Sher Shah Suri, came to obtain the blessings of Guru Angad in regaining the throne of Delhi.

Guru Amaru Das ji

Guru Amaru Das ji became the third Sikh guru in 1552 at the age of 73. Goindwal became an important centre for Sikhism during the Guruship of Guru Amar Das. He continued to preach the principle of equality for women, the prohibition of Sati and the practise of Langar.[4] In 1567, Emperor Akbar sat with the ordinary and poor people of Punjab to have Langar. Guru Amar Das also trained 140 apostles, of which 52 were women, to manage the rapid expansion of the religion.[5] Before he died in 1574 aged 95, he appointed his son-in-law Jetha as the fourth Sikh Guru.

It is recorded that before becoming a Sikh, Bhai Amar Das, as he was known at the time, was a very religious Vaishanavite Hindu who spent most of his life performing all of the ritual pilgrimages and fasts of a devout Hindu. One day, Bhai Amar Das heard some hymns of Guru Nanak being sung by Bibi Amro Ji, the daughter of Guru Angad, the second Sikh Guru. Bibi Amro was married to Bhai Sahib's brother, Bhai Manak Chand's son who was called Bhai Jasso. Bhai Sahib was so impressed and moved by these Shabads that he immediately decided to go to see Guru Angad at Khadur Sahib. It is recorded that this event took place when Bhai Sahib was 61 years old.

In 1635, upon meeting Guru Angad, Bhai Sahib was so touched by the Guru's message that he became a devout Sikh. Soon he became involved in Sewa (Service) to the Guru and the Community. Under the impact of Guru Angad and the teachings of the Gurus, Bhai Amar Das became a devout Sikh. He adopted Guru as his spiritual guide (Guru). Bhai Sahib began to live at Khadur Sahib, where he used to rise early in the morning and bring water from the Beas River for the Guru's bath; he would wash the Guru's clothes and fetch wood from the jungle for 'Guru ka Langar'. He was so dedicated to Sewa and the Guru and had completely extinguished pride and was totally lost in this commitment that he was considered an old man who had no interest in life; he was dubbed Amru, and generally forsaken.

However, as a result of Bhai Sahib's commitment to Sikhi principles, dedicated service and devotion to the Sikh cause, Guru Angad Sahib appointed Guru Amar Das Sahib as third Nanak in March 1552 at the age of 73. He established his headquarters at the newly built town of Goindwal, which Guru Angad had established.

Soon large numbers of Sikhs started flocking to Goindwal to see the new Guru. Here, Guru Amar Das propagated the Sikh faith in a vigorous, systematic and planned manner. He divided the Sikh Sangat area into 22 preaching centres or Manjis, each under the charge of a devout Sikh. He himself visited and sent Sikh missionaries to different parts of India to spread Sikhism.

Guru Amaru Das ji was impressed with Bhai Gurdas' thorough knowledge of Hindi and Sanskrit and the Hindu scriptures. Following the tradition of sending out Masands across the country, Guru Amar Das deputed Bhai Gurdas to Agra to spread the gospel of Sikhism. Before leaving, Guru Amar Das prescribed the following routine for Sikhs:

Guru Ji strengthened the tradition of 'Guru ka Langar' and made it compulsory for the visitor to the Guru to eat first, saying that 'Pehle Pangat Phir Sangat' (first visit the Langar then go to the Guru). Once the emperor Akbar came to see Guru Sahib and he had to eat the coarse rice in the Langar before he could have an interview with Guru Sahib. He was so much impressed with this system that he expressed his desire to grant some royal property for 'Guru ka Langar', but Guru Sahib declined it with respect.

He introduced new birth, marriage and death ceremonies. Thus he raised the status of women and protected the rights of female infants who were killed without question as they were deemed to have no status. These teachings met with stiff resistance from the Orthodox Hindus. He fixed three Gurpurbs for Sikh celebrations: Diwali, Vaisakhi and Maghi.

Guru Amaru Das ji not only preached the equality of people irrespective of their caste but he also fostered the idea of women's equality. He preaching strongly against the practice of Sati (a Hindu wife burning on her husband's funeral pyre). Guru Amar Das also disapproved of a young widow remaining unmarried for the rest of her life.

Guru Amaru Das ji constructed "Baoli" at Goindwal Sahib having eighty-four steps and made it a Sikh pilgrimage centre for the first time in the history of Sikhism. He reproduced more copies of the hymns of Guru Nanak and Guru Angad. He also composed 869 (according to some chronicles these were 709) verses (stanzas) including Anand Sahib, and then later on Guru Arjan (fifth Guru) made all the Shabads part of Guru Granth Sahib.

When it came time for the Guru's younger daughter Bibi Bhani to marry, he selected a pious and diligent young follower of his called Jetha from Lahore. Jetha had come to visit the Guru with a party of pilgrims from Lahore and had become so enchanted by the Guru's teachings that he had decided to settle in Goindwal. Here he earned a living selling wheat and would regularly attend the services of Guru Amar Das in his spare time.

Guru Amaru Das ji did not consider anyone of his sons fit for Guruship and chose instead his son-in law (Guru) Ram Das to succeed him. Guru Amar Das Sahib at the age of 95 died on 1 September 1574 at Goindwal in District Amritsar, after giving responsibility of Guruship to the Fourth Nanak, Guru Ram Das.

Sri Guru Ram Das ji

Sri Guru Ram Das ji (Punjabi: ਗੁਰੂ ਰਾਮ ਦਾਸ) (Born in Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan on 24 September 1534 – 1 September 1581, Amritsar, Punjab, India) was the fourth of the Ten Gurus of Sikhism, and he became Guru on 30 August 1574, following in the footsteps of Guru Amar Das. His wife was Bibi Bhani, the younger daughter of Guru Amar Das, the third guru of the Sikhs. As a Guru one of his main contributions to Sikhism was organizing the structure of Sikh society. Additionally, he was the author of Laava, the hymns of the Marriage Rites, the designer of the Harmandir Sahib, and the planner and creator of the township of Ramdaspur (later Amritsar).

Sri Guru Arjan Dev ji

In 1581, Sri Guru Arjan Dev ji — the youngest son of the fourth guru — became the Fifth Guru of the Sikhs. In addition to being responsible for building the Golden Temple, he prepared the Sikh Sacred text and his personal addition of some 2,000 plus hymns in the Gurū Granth Sāhib.

In 1604 he installed the Ādi Granth for the first time. In 1606, for refusing to make changes to the Gurū Granth Sāhib, he was tortured and killed by the Mughal rulers of the time.[3]

Sri Satguru Hare-Gobind Sahib ji

Sri Satguru Hare-Gobind Sahib ji became the sixth guru of the Sikhs. He carried two swords — one for Spiritual reasons and one for temporal (worldly) reasons.[6] From this point onward, the Sikhs became a military force and always had a trained fighting force to defend their independence.

Sri Satguru Hare-Gobind Sahib ji fixed two Nishan Sahib's at Akal Bunga in front of the Akal Takht. One flag is towards the Harmandir Sahib and the other shorter flag is towards Akal Takht. The first represents the reins of the spiritual authority while the later represents temporal power stating temporal power should be under the reins of the spiritual authority.

Guru Har Rai

Guru Har Rai (Punjabi: ਗੁਰੂ ਹਰਿ ਰਾਇ) (26 February 1630 - 6 October 1661) was the seventh of the ten Gurus of Sikhism, becoming Guru on 8 March 1644, following in the footsteps of his grandfather, Guru Har Gobind, who was the sixth guru. Before he died, he appointed Guru Har Krishan, his youngest son, as the next Guru of the Sikhs.

As a very young child he was disturbed by the suffering of a flower damaged by his robe in passing. Though such feelings are common with children, Guru Har Rai would throughout his life be noted for his compassion for life and living things. His grandfather, who was famed as an avid hunter, is said to have saved the Moghul Emperor Jahangir's life during a tiger's attack. Guru Har Rai continued the hunting tradition of his grandfather, but he would allow no animals to be killed on his grand Shikars. The Guru instead captured the animal and added it to his zoo. He made several tours to the Malwa and Doaba regions of the Punjab.

His son, Ram Rai, seeking to assuage concerns of Aurangzeb over one line in Guru Nanak's verse (Mitti Mussalmam ki pede pai kumhar) suggested that the word Mussalmam was a mistake on the copyist's part, therefore distorting Bani. The Guru refused to meet with him again. The Guru is believed to have said, "Ram Rai, you have disobeyed my order and sinned. I will never see you again on account of your infidelity." It was also reported to the Guru that Ram Rai had also worked miracles in the Mughal's court against his father's direct instructions. Sikhs are constrained by their Gurus to not believe in magic and myth or miracles. Just before his death at age, 31, Guru Har Rai passed the Gaddi of Nanak on to his younger son, the five year old — Guru Har Krishan.

Guru Har Rai was the son of Baba Gurdita and Mata Nihal Kaur (also known as Mata Ananti Ji). Baba Gurdita was the son of the sixth Guru, Guru Hargobind. Guru Har Rai married Mata Kishan Kaur (sometimes also referred to as Sulakhni), daughter of Sri Daya Ram of Anoopshahr (Bulandshahr) in Uttar Pradesh on Har Sudi 3, Samvat 1697. Guru Har Rai had two sons: Baba Ram Rai and Sri Har Krishan.

Although, Guru Har Rai was a man of peace, he never disbanded the armed Sikh Warriors (Saint Soldiers), who earlier were maintained by his grandfather, Guru Hargobind. He always boosted the military spirit of the Sikhs, but he never himself indulged in any direct political and armed controversy with the contemporary Mughal Empire. Once, Dara Shikoh (the eldest son of emperor Shah Jahan), came to Guru Har Rai asking for help in the war of succession with his brother, the murderous Aurangzeb. The Guru had promised his grandfather to use the Sikh Cavalry only in defence. Nevertheless, he helped him to escape safely from the bloody hands of Aurangzeb's armed forces by having his Sikh warriors hide all the ferry boats at the river crossing used by Dara Shikoh in his escape.

Guru Har Krishan

Guru Har Krishan born in Kirat Pur, Ropar (Punjabi: ਗੁਰੂ ਹਰਿ ਕ੍ਰਿਸ਼ਨ) (7 July 1656 - 30 March 1664) was the eighth of the Ten Gurus of Sikhism, becoming the Guru on 7 October 1661, following in the footsteps of his father, Guru Har Rai. Before Har Krishan died of Smallpox, he nominated his granduncle, Guru Teg Bahadur, as the next Guru of the Sikhs. The following is a summary of the main highlights of his short life:

When Har Krishan stayed in Delhi there was a smallpox epidemic and many people were dying. According to Sikh history at Har Krishan's blessing, the lake at Bangla Sahib provided cure for thousands. Gurdwara Bangla Sahib was constructed in the Guru's memory. This is where he stayed during his visit to Delhi. Gurdwara Bala Sahib was built in south Delhi besides the bank of the river Yamuna, where Har Krishan was cremated at the age of about 7 years and 8 months. Guru Har Krishan was the youngest Guru at only 7 years of age. He did not make any contributions to Gurbani.

Guru Tegh Bahadur

Guru Tegh Bahadur is the ninth of the Sikh Gurus. Guru Tegh Bahadur sacrificed himself to protect Hindus. He was asked by Aurungzeb, the Mughal emperor, under coercion by Naqshbandi Islamists, to convert to Islam or to sacrifice himself. The exact place where he attained martyrdom is in front of the Red Fort in Delhi (Lal Qila) and the gurdwara is called Sisganj.[7] This marked a turning point for Sikhism. His successor, Guru Gobind Singh further militarised his followers.

Guru Gobind Singh

Guru Gobind Singh was the tenth guru of Sikhs. He was born in 1666 at Patna (Capital of Bihar, India). In 1675 Pundits from Kashmir in India came to Anandpur Sahib pleading to Guru Teg Bhadur (Father of Guru Gobind Singh ) about Aurangzeb forcing them to convert to Islam. Guru Teg Bahadur told them that martyrdom of a great man was needed. His son, Guru Gobind Singh said "Who could be greater than you", to his father. Guru Teg Bahadur told pundits to tell Aurangzeb's men that if Guru Teg Bahadur will become Muslim, they all will. Guru Teg Bahadur was then martyred in Delhi, but before that he assigned Guru Gobind Singh as 10th Guru at age of 9. After becoming Guru he commanded Sikhs to be armed. He fought many battles with Aurangzeb and some other Kings of that time, and always remained victorious.Template:Fix

Creation of the Khalsa

In 1699 he created the Khalsa panth, by giving amrit to sikhs. In 1704 he fought the great battle with collective forces of Aurangzeb, Wazir Khan (Chief of Sarhind), and other kings. He left Anandpur and went to Chamkaur with only 40 sikhs. There he fought the Battle of Chamkaur with 40 sikhs, vastly outnumbered by the Mughal soldiers. His two elder sons (at ages 17, 15) were martyred there. Wazir Khan killed other two (ages 9, 6). Guru Ji sent Aurangzeb the Zafarnamah (Notification of Victory). Then he went to Nanded (Maharashtra, India). From there he made Baba Gurbakhash Singh, also aliased as Baba Banda Singh Bahadur, as his general and sent him to Punjab.

On the evening of the day when Baba Gurbakhash Singh left for Punjab, Guru Gobind Singh was visited by two Muslim soldiers. One of them was commissioned by Wazir Khan, Subedar of Sirhind, to assassinate Guru Gobind Singh. One of the assailants, Bashal Beg, kept a vigil outside the Guru's tent while Jamshed Khan, a hired assassin, stabbed the Guru twice. Khan was killed in one stroke by the Guru, while those outside, alerted by the tumult, killed Beg. Although the wound was sewn up the following day, the Guru died in Nanded, Maharashtra, India in 1708.[8]

Shortly before passing away Guru Gobind Singh ordered that the Guru Granth Sahib (the Sikh Holy Scripture), would be the ultimate spiritual authority for the Sikhs and temporal authority would be vested in the Khalsa Panth – the Sikh Nation. The first Sikh Holy Scripture was compiled and edited by the Fifth Guru, Guru Arjan in AD 1604, although some of the earlier gurus are also known to have documented their revelations. This is one of the few scriptures in the world that has been compiled by the founders of a faith during their own lifetime. The Guru Granth Sahib is particularly unique among sacred texts in that it is written in Gurmukhi script but contains many languages including Punjabi, Hindustani, Sanskrit, Bhojpuri, Assamese and Persian. Sikhs consider the Guru Granth Sahib the last, perpetual living guru.

Banda Singh Bahadur

Banda Singh Bahadur was chosen to lead the Sikhs by Guru Gobind Singh[9]. He was successful in setting up a Sikh Empire that spread from Uttar Pradesh to Punjab. He fought the Islamist Mughal state tyranny and gave the common people of Punjab courage, equality, and rights.[10][11] On his way to Punjab, Banda Singh punished robbers and other criminal elements making him popular with the people.[12] Banda Singh inspired the minds of the non-Muslim people, who came to look upon the Sikhs as defenders of their faith and country.[13] Banda Singh possessed no army but Guru Gobind Singh in a Hukamnama called to the people of Punjab to take arms under the leadership of Banda Singh overthrow and destroy the oppressive Mughal rulers[14], oppressed Muslims and oppressed Hindus also joined him in the popular revolt against the tyrants.[15]

Banda Singh Bahadur camped in Khar Khoda, near Sonipat from there he took over Sonipat and Kaithal.[16] In 1709 Banda Singh captured the Mughal city of Samana with the help of revolting oppressed Hindu and common folk, killing about 10,000 Mohammedans.[17][18] Samana which was famous for minting coins, with this treasury the Sikhs became financially stable. The Sikhs soon took over Mustafabad[19] and Sadhora (near Jagadhri).[20] The Sikhs than captured the Cis-Sutlej areas of Punjab including Ghurham, Kapori, Banoor, Malerkotla, and Nahan. The Sikhs captured Sirhind in 1710 and killed the Governer of Sirhind, Wazir Khan who was responsible for the martyrdom of the the two youngest sons of Guru Gobind Singh at Sirhind. Becoming the ruler of Sirhind Banda Singh gave order to give ownership of the land to the farmers and let them live in dignity and self-respect.[21] Petty officials were also satisfied of with the change. Dindar Khan, an official of the nearby village, took Amrit and became Dinder Singh and the newspaper writer of Sirhind, Mir Nasir-ud-din, became Mir Nasir Singh[22]

Banda Singh developed a the village of Mukhlisgarh, and made it his capital He then renamed the city it to Lohgarh (fortress of steel) where he issued his own mint.[23]. The coin described Lohgarh: "Struck in the City of Peace, illustrating the beauty of civic life, and the ornament of the blessed throne." He briefly established a state in Punjab for half a year. Banda Singh sent Sikhs to the Uttar Pradesh and Sikhs took over Saharanpur, Jalalabad, Saharanpur, and other areas near by bringing relief to the repressed population.[24] In the regions of Jalandharand Amritsar, the Sikhs started fighting for the rights of the people. They used their newly established power to remove corrupt officials and replace them with honest ones.[25]

Banda Singh Bahadur ji is known to have abolished or halted the Zamindari system in time he was active and gave the farmers proprietorship of their own land.[26] It seems that all classes of government officers were addicted to extortion and corruption and the whole system of regulatory and order was subverted.[27] Local tradition recalls that the people from the neighborhood of Sadaura came to Banda Singh complaining of the iniquities practices by their land lords. Banda Singh ordered Baj Singh to open fire on them. The people were astonished at the strange reply to their representation, and asked him what he meant. He told them that they deserved no better treatment when being thousands in number they still allowed themselves to be cowed down by a handful of Zamindars.[28]

The rule of the Sikhs over the entire Punjab east of Lahore obstructed the communication between Delhi and Lahore, the capital of Punjab, and this worried Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah He gave up his plan to subdue rebels in Rajasthan and marched towards Punjab.[29] The entire Imperial force was organized to defeat and kill Banda Singh.[30] All the generals were directed to join the Emperor’s army. To ensure that there were no Sikh agents in the army camps, an order was issued on August 29, 1710 to all Hindus to shave off their beards.[31]

Banda Singh was in in Uttar Pradesh when the Moghal army under the orders of Munim Khan[32] marched to Sirhind and before the return of Banda Singh, they had already taken Sirhind and the areas around it. The Sikhs therefore moved to Lohgarh for their final battle. The Sikhs defeated the the army but reinforcements were called and they laid siege on the fort with 60,000 troops.[33][34] Gulab Singh dressed himself in the garments of Banda Singh and seated himself in his place.[35] Banda Singh left the fort at night and went to a secret place in the hills and Chamba forests. The failure of the army to kill or catch Banda Singh shocked Emperor, Bahadur Shah and On 10 December 1710 he ordered that wherever a Sikh was found, he should be murdered.[36] The Emperor became mentally disturbed and died on February 18 1712.[37]

Banda Singh Bahadur wrote Hukamnamas to the Sikhs telling them to get themselves reorganized and join him at once.[38] In 1711 the Sikhs gathered near Kiratpur Sahib and defeated Raja Bhim Chand[39], who was responsible for organizing all the Hill Rajas against Guru Gobind Singh and instigating battles with him. After Bhim Chand’s dead the other Hill Rajas accepted their subordinate status and paid revenues to Banda Singh. While Bahadur Shah's 4 sons were killing themselves for the throne of the Mughal Emperor[40] Banda Singh Bahadur recaptured Sadhura and Lohgarh. Farrukh Siyar, the next Moghal Emperor, appointed Abdus Samad Khan as the governor of Lahore and Zakaria Khan, Abdus Samad Khan's son, the Faujdar of Jammu.[41] In 1713 the Sikhs left Lohgarh and Sadhura and went to the remote hills of Jammu and where they built Dera Baba Banda Singh.[42] During this time Sikhs were being hunted down especially by pathans in the Gurdaspur region.[43] Banda Singh came out and captured Kalanaur and Batala[44] which rebuked Farrukh Siyar to issue Mughal and Hindu officals and chiefs to proceed with their troops to Lahore to reinforce his army.[45]

In March 1715, Banda Singh Bahadur was in the village of Gurdas Nangal, Gurdaspur, Punjab, when the army under the rule of Samad Khan[46], the Mogual king of Delhi laid siege to the Sikh forces.[47] The Sikhs fought and defended the small fort for eight months.[48] In December 7 1715 Banda Singh starving soldiers were captured.

Execution

On December 7 1715 Banda Singh Bahadur was captured from the Gurdas Nangal fort and put in an iron cage and the remaining Sikhs were captured, chained.[49] The Sikhs were bought to Delhi in a procession with the 780 Sikh prisoners, 2,000 Sikh heads hung on spears, and 700 cartloads of heads of slaughtered Sikhs used to terrorize the population.[50][51] They were put in the Delhi fort and pressured to give up their faith and become Muslims.[52] On their firm refusal all of them were ordered to be executed. Every day, 100 Sikhs were brought out of the fort and murdered in public daily[53] , which went on approximately seven days. The Mussalmans could hardly contain themselves of joy while the Sikhs showed no sign of dejection or humiliation, instead they sang their sacred hymns; none feared dead or gave up their faith.[54] After 3 months of confinement[55] On June 9 1716, Banda Singh’s eyes were gouged, his limbs were severed, his skin removed, and then he was killed.[56]

Sikhs retreat to Jungles.

In 1716 ca. Farrukh Siyar, the Mughal Emperor, issued all Sikhs to be converted to Islam or die, an attempt to destroy the power of the Sikhs and to exterminate the community as a whole.[57] A reward was offered for the head of every Sikh.[58] For a time it appeared as if the boast of Farrukh Siyar to wipe out the name of Sikhs from the land was going to be fulfilled. Hundreds of Sikhs were brought in from their villages and executed, and thousands who had joined merely for the sake of booty cut off their hair and went back to the Hindu fold again.[59] Besides these there were some Sikhs who had not yet received the baptism of Guru Gobind Singh, nor did they feel encouraged to do so, as the adoption of the outward symbols meant courting death.

After a few years Adbus Samad Khan, the Governor of Lahore, Punjab and other Mughal officers began to pursuit Sikhs less and thus the Sikhs came back to the villages and started going to the Gurdwaras again,[60] which were managed by Udasis when the Sikhs were in hiding. The Sikhs celebrated Diwali and Vaisakhi at Harmandir Sahib. The Khalsa had been split into two major fractions Bandia Khalsa and Tat Khalsa and tensions were spewing between the two.

Under the authority of Mata Sundari Bhai Mani Singh become the Jathedar of the Harminder Sahib[61] and a leader of the Sikhs and the Bandia Khalsa and Tat Khalsa joined by Bhai Mani Singh into the Tat Khalsa[62] and after the event from that day the Bandeis assumed a quieter role and practically disappeared from the pages of history. A police post was established at Amritsar to keep a check on the Sikhs.[63]

Abdus Samad Khan, was transferred to Multan in 1726, and his more energetic Son, Zakaria Khan, also known as Khan Bahadur[64], was appointed to take his place as the governor of Lahore. In 1726, Tarra Singh of Wan, a renowned Sikh leader, and his 26 men was killed after Governor Zakaria Khan, sent 2200 horses, 40 zamburaks, 5 elephants and 4 cannons, under the command of his deputy, Momim Khan.[65] The murder of Tarra Singh spread across the Sikhs in Punjab and the Sikhs. Finding no Sikhs around, the government falsely announced in each village with the beat of a drum, that all Sikhs had been eliminated but the common people knew the truth that this was not the case.[66] The Sikhs did not face the army directly, because of their small numbers, but adopted dhai phut guerrilla warfare (hit and run) tactics.

Under the leadership of Nawab Kapoor Singh and Jathedar Darbara Singh, in attempt to weaken their enemy looted many of the Mughals caravans and supplies and for some years no money from revenue could reach the government treasury.[67] When the forces of government tried to punish the outlaws, they were unable to contact them, as the Sikhs did not live in houses or forts, but ran away to their rendezvous in forests or other places difficult to access.

Age of Revolution (1750 CE – 1914 CE)

Nawab Kapur Singh

Nawab Kapur Singh was born in 1697 in a village near Sheikhupura, Punjab, Pakistan. He was given a jagir in 1733 when the Governor of Punjab offered the Sikhs the Nawabship (ownership of an estate) and a valuable royal robe, the Khalsa accepted it all in the name of Kapur Singh.[68] Henceforth, he became known as Nawab Kapur Singh. In 1748 he would organize the early Sikh Misls into the Dal Khalsa (Budda Dal and Tarna Dal).[69]

Nawab Kapur Singh’s father was Chaudhri Daleep Singh as a boy he memorized Gurbani Nitnem and was taught the arts of war.[70] Kapur Singh was attracted to the Khalsa Panth after the execution of Bhai Tara Singh, of the village of Van, in 1726.[71]

Extensive Looting of the Mughal Government

The Khalsa held a meeting to make plans to respond to the state repression against the people of the region and they decided to take procession of government money and weapons in order to weaken the administration, and to equip themselves to face the everyday attacks.[72] Kapur Singh was assigned to plan and execute these projects.

Information was obtained that money was being transported from Multan to the Lahore treasure; the Khalsa looted the money and took over the arms and horses of the guards.[73] They then took over one lakh rupees from the Kasoor estate treasury going from Kasur to Lahore.[74] Next they captured a caravan from Afghanistan region which resulted in capturing numerous arms and horses. The Khalsa siezed a number of vilayati (Superior Central Asian) horses from Murtaza Khan was going to Delhi in the jungle of Kahna Kachha.[75][76] Some additional war supplies were being taken from Afghanistan to Delhi and Kapur Singh organized an attack to capture them. In another attack the Khalsa recovered gold and silver which was intended to being carried from Peshawar to Delhi by Jaffar Khan, a royal official.[77]

Government Sides with The Khalsa

The Mughal rulers and the commanders alongside the Delhi government lost all hope of defeating the Sikhs through repression and decided to develop another strategy, Zakaria Khan, the Governor of Lahore, went to Delhi where it was decided to befriend the Sikhs and rule in cooperation with them and in 1733 the Dehli rulers withdrew all orders against the Khalsa.[78] The Sikhs were now permitted to own land and to move freely without any state violence against them.[79] To co-operate with the Khalsa Panth, and win the goodwill of the people, the government sent an offer of an estate and Nawabship through a famous Lahore Sikh, Subeg Singh.[80] The Khalsa did not wanted to rule freely and not to be under the rule of a subordinate position. However this offer was eventually accepted and this title was bestowed on Kapur Singh after it was sanctified by the touch of Five Khalsas feet.[81] Thus Kapur Singh became Nawab Kapur Singh. Kapur Singh guided the Sikhs in strengthening themselves and preaching Gurmat to the people. He knew that peace would be short lived. He encouraged people to freely visit their Gurdwaras and meet their relatives in the villages.[82]

Dal Khalsa

The Khalsa reorganized themselves into two divisions, the younger generation would be part of the Taruna Dal, which provided the main fighting force, while the Sikhs above the age of forty years would be a part of the Budha Dal, which provided the responsibility of the management of Gurdwaras and Gurmat preaching.[83] The Budha Dal would be responsible to keep track of the movements of government forces, plan their defense strategies, and they provide a reserve fighting force for the Taruna Dal.[84]

The following measures were established by Nawab Kapur Singh:[85]

- All money obtained from anywhere by any Jatha should be deposited in the Common Khalsa Fund.

- The Khalsa should have their common Langer for both the Dals.

- Every Sikh should respect the orders of his Jathedar. Anyone going anywhere would get permission from him and report to him on his return.

5 Sikh Misls of the Dal Khalsa

The Taruna Dal quickly increased to more than 12,000 recruits and it soon became difficult to manage the house and feeding of such a large number of people at one place.[86] It was then decided to have five divisions of the Dal, each to draw rations from the central stocks and cook it’s own langar.[87] These five divisions were stationed around the five sarovars (sacred pools) around Amritsar they were Ramsar, Bibeksar, Lachmansar, Kaulsar and Santokhsar.[88] The divisions later became known as Misls and their number increased to eleven. Each took over and ruled a different region of the Punjab. Collectively they called themselves the Sarbat Khalsa.

Preparing Jassa Singh Ahluwalia for leadership

Being the leader of the Khalsa Nawab Kapur Singh was given an additional responsibility by Mata Sundari, the wife of Guru Gobind Singh sent Kapur Singh the young Jassa Singh Ahluwalia and told him that Ahluwalia was like a son to her and that the Nawab should raise him like an ideal Sikh. Ahluwalia under the guidance of Kapur Singh, was given a good education in Gurbani and a thorough training in managing the Sikh affairs.[89] Later Jassa Singh Ahluwalia would become an important role in leading the Sikhs to self-rule.

State Oppression

In 1735, the rulers of Lahore attacked and repossessed the jagir (estate) given to the Sikhs only two years before[90] however Nawab Kapur Singh in reaction decided the whole Punjab should be taken over by the Sikhs.[91] This decision was taken against heavy odds but was endorsed by the Khalsa and all the Sikhs assured him of their full cooperation in his endeavor for self-rule. Zakaria Khan sent roaming squads to hunt and kill the Sikhs. Orders were issued to all administrators down to the village level officials to seek Sikhs, murder them, get them arrested, or report their whereabouts to the governments. One years wages were offered to anyone who would murder a Sikh and deliver his head to the police station.[92] Rewards were also promised to those who helped arrest Sikhs. Persons providing food or shelter to Sikhs or helping them in any way were severely punished.[93]

This was the period when the Sikhs were sawed into pieces,[94] burnt alive,[95] their heads crushed with hammers[96] and young children were pierced with spears before their mother’s eyes.[97] To keep their morale high, the Sikhs developed their own high-sounding terminologies and slogans:[98] For example. Tree leaves boiled for food were called ‘green dish’; the parched chickpeas were called ‘almonds’; the Babul tree was a ‘rose’; a blind man was a ‘brave man’, getting on the back of a buffalo was ‘riding an elephant’.

The army pursued the Sikhs hiding near the hills and forced them to cross the rivers and seek safety in the Malwa tract.[99] When Kapur Singh reached Patiala he met Maharaja Baba Ala Singh who then took Amrit[100] and Kapur Singh helped him increase the boundaries of his state. In 1736 the Khalsa attacked Sirhind, where the two younger sons of Guru Gobind Singh were martyred. The Khalsa took over the city, the took over the treasury and they established the Gurdwaras at the historical places and withdrew.[101] While near Amritsar the government of Lahore sent troops to attack the Sikhs. Kapur Singh entrusted the treasury to Jassa Singh Ahluwalia, while having sufficient amount of Sikhs with him to keep the army engaged. When Jassa Singh was reached a consider distance the Khalsa safely retreated to Tarn Taran Sahib. Kapur Singh sent messages to the Tauna Dal asking them to help them in the fight. After a days of fighting Kapur Singh from the trenches dug by the Khalsa surprisingly attacked the commanding posts killing three generals alongside many Mughal officers. The Mughal army thus retreated to Lahore.

Zakaria Khan called his advisers to plan another strategy to deal with the Sikhs. It was suggested that the Sikhs should not be allowed to visit the Amrit Sarovar,[102] which was believed to be the fountain of their lives and source of their strength. Strong contingents were posted around the city and all entries to Harmandir Sahib were checked. The Sikhs, however, risking their lives, continued to pay their respects to the holy place and take a dip in the Sarovar (sacred pool) in the dark of the night. When Kapur Singh went to Amritsar he had a fight with Qadi Abdul Rehman. He had declared that Sikhs the so-called lions, would not dare to come to Amritsar and face him. In the ensuing fight Abdul Rehman was killed.[103] When his son tried to save him, he too lost his life. In 1738 Bhai Mani Singh was executed.

Sikhs attack Nader Shah

In 1739 Nader Shah of the Turkic Afsharid dynasty invaded and looted the treasury of the Indian subcontinent. Nader Shah killed more than 100,000 people in Delhi and carried off all of the gold and valuables.[104] He added to his caravan hundreds of elephants and horses, along with thousands of young women and Indian artisans.[105] When Kapur Singh came to know of this, he decided to warn Nader Shah that if not the local rulers, then the Sikhs would protect the innocent women of Muslims and Hindus from being sold as slaves. While crossing The river Chenab, the Sikhs attacked the rear end of the caravan, freed many of the women, freed the artisans, and recovered part of the treasure.[106] The Sikhs continued to harass him and lighten him of his loot until he withdrew from the Punjab.

Sikhs kill Massa Rangar

Massa Rangar, the Mughal Official, had token over the control of Amritsar. While smoking and drinking in the Harmandir Sahib, he watched the dances of nautch girls.[107] The Sikhs who had moved to Bikaner, a desert region, for safety, were outraged to hear of this desecration. In 1740 Sukha Singh and Mehtab Singh, went to Amritsar disguised as revenue collectors.[108] They tied their horses outside, walked straight into the Harmandir Sahib, cut off his head,[109] and took it with them. It was a lesson for the ruler that no tyrant would go unpunished.

Sikhs loot Abdus Samad Khan

Abdus Samad Khan, a senior Mughal royal commander, was sent from Delhi to subdue the Sikhs.[110] Kapur Singh learned of this scheme and planned his own strategy accordingly. As soon as the army was sent out to hunt for the Sikhs, a Jatha of commandos disguised as messengers of Khan went to the armory. The commander there was told that Abdus Samad Khan was holding the Sikhs under siege and wanted him with all his force to go and arrest them. The few guards left behind were then overpowered by the Sikhs, and all the arms and ammunition were looted and brought to the Sikh camp.[111]

Mughals increase persecution

Abdus Samad Khan sent many roaming squads to search for and kill Sikhs. He was responsible for the torture and murder of Bhai Mani Singh,[112] the head Granthi of Harimander Sahib. Samad Khan was afraid that Sikhs would kill him so he remained far behind the fighting lines.[113] Kapur Singh had a plan to get him. During the battle Kapur Singh ordered his men to retreat drawing the fighting army with them. He then wheeled around and fell upon the rear of the army.[114] Samad Khan and his guards were lying dead on the field within hours. The Punjab governor also was took extra precautions for safety against the Sikhs. He started to live in the fort. He would not even dare to visit the mosque outside the fort for prayers.

On the request of the Budha Dal members, Kapur Singh visited Patiala. The sons of Sardar Ala Singh, the founder and Maharajah of the Patiala state, gave him a royal welcome. Kapur Singh subdued all local administrators around Delhi who were not behaving well towards their people.

Zakaria Khan died in 1745. His successor tightened the security around Amritsar. Kapur Singh planned to break the siege of Amritsar. Jassa Singh Ahluwalia was made the commander of the attacking Sikh forces. In 1748, the Sikhs attacked. Jassa Singh Ahluwalia, with his commandos behind him, dashed to the army commander and cut him into two with his sword. The commander's nephew was also killed.

The Khalsa strengthen military developments

The Sikhs built their first fort Ram Rauni at Amritsar in 1748.[115] In December 1748, Governor Mir Mannu had to take his forces outside of Lahore to stop the advance of Ahmad Shah Abdali. The Sikhs quickly overpowered the police defending the station in Lahore and confiscated all of their weapons and released all the prisoners.[116] Nawab Kapur Singh told the sheriff to inform the Governor that, the sheriff of God, the True Emperor, came and did what he was commanded to do. Before the policemen could report the matter to the authorities, or the army could be called in, the Khalsa were already riding their horses back to the forest.[117] Nawab Kapur Singh died in 1753.

Jassa Singh Ahluwalia

Jassa Singh Ahluwalia was born in 1718. His father, Badar Singh, died when Ahluwalia was only four years old.[118] His mother took him to Mata Sundari, the wife of Guru Gobind Singh when Ahluwalia was young.[119][120]. Mata Sundri was impressed by his melodious singing of hymns and kept the Ahluwalia near hear. Later Jassa Singh Ahluwalia was adopted by Nawab Kapoor Singh[121], then the leader of the Sikh nation. Ahluwalia followed all Sikh qualities required for a leader Ahluwalia would sing Asa di Var in the morning and it was appreciated by all the Dal Khalsa and Ahluwalia kept busy doing seva (selfless service). He became very popular with the Sikhs. He used to tie his turban in the Mughal fashion as he grew up in Delhi. Ahluwalia learned horseback riding and swordsmanship from expert teachers.[122]

In 1748 Jassa Singh Ahluwalia became the supreme commander of all the Misls.[123] Jassa Singh Ahluwalia was honored with the title of Sultanul Kaum (King of the Nation).[124] Jassa Singh Ahluwalia was the head of the Ahluwalia Misl and then after Nawab Kapoor Singh become the leader of all the Misls jointly called Dal Khalsa. He played a major role In leading the Khalsa to self-rule in Punjab. In 1761 The Dal Khalsa under the leadership of Ahluwalia, would take over Lahore, the capital of Punjab, for the first time.[125] The were the masters of Lahore for a few months and minted their own Nanakshahi rupee coin in the name of 'Guru Nanak - Guru Gobind Singh'.[126]

Chhota Ghalughara (The Lesser Massacre)

In 1746 about seven thousand Sikhs were killed and three thousand to fifteen thousand[127] Sikhs were taken prisoners during by the order of the Mughal Empire when Zakaria Khan, The Governor of Lahore, and Lakhpat Rai, the Divan (Revenue Minister) of Zakaria Khan, sent military squads to kill the Sikhs.[128][129]

Jaspat Rai, a jagirdar (landlord) of the Eminabad area and also the brother of Lakhpat Rai, faced the Sikhs in a battle one of the Sikhs held the tail of his elephant and got on his back from behind and with a quick move, he chopped off his head.[130] Seeing their master killed, the troops fled. Lakhpat Rai, after this incident, committed himself to destroying the Sikhs.[131]

Through March-May 1746, a new wave of violence was started against the Sikhs with all of the resources available to the Mughal government, village officials were ordered to co-operate in the expedition. Zakaria Khan issued the order that no one was to give any help or shelter to Sikhs and warned that severe consequences would be taken against anyone disobeying these orders.[132] Local people were forcibly employed to search for the Sikhs to be killed by the army. Lakhpat Rai ordered Sikh places of worship to be destroyed and their holy books burnt.[133] Information about including Jassa Singh Ahluwalia and a large body of Sikhs were camping in riverbeds in the Gurdaspur district (Kahnuwan tract). Zakaria Khan managed to have 3,000 Sikhs of these Sikhs captured and later got them beheaded in batches at Nakhas (site of the horse market outside the Delhi gate).[134] Sikhs raised a memorial shrine known as the Shahidganj (the treasure house of martyrs) at that place latter.

In 1747, Shah Nawaz took over as Governor of Lahore. To please the Sikhs, Lakhpat Rai was put in prison by the new Governor.[135] Lakhpat Rai received severe punishment and was eventually killed by the Sikhs.

Reclaiming Amritsar

In 1747 Salabat Khan, a newly appointed Mughal commander, placed police around Amritsar and built observation posts to spot and kill Sikhs coming to the Amrit Sarovar for a holy dip.[136] Jassa Singh Ahluwalia and Nawab Kapoor Singh lead the Sikhs to Amritsar and Salabat Khan was killed by Ahluwalia and his nephew was killed by the arrow of Kapur Singh.[137][138] The Sikhs restored Harmandir Sahib and celebrated their Diwali gathering there.

Reorganization of the Misls

In 1748 all the Misls joined themselves under one command and on the advice of the aging Jathedar Nawab Kapoor Singh Jassa Singh Ahluwalia was made the supreme leader.[139] They also decided to declare that the Punjab belonged to them and they would be the sovereign rulers of their state. The Sikhs also built their first fort, called Ram Rauni, at Amritsar.

Khalsa side with the Government

Adina Beg, the Faujdar (garrison commander) of Jalandhar, sent a message to the Dal Khalsa chief to cooperate with him in the civil administration, and he wanted a meeting to discuss the matter.[140] This was seen as a trick to disarm the Sikhs and keep them under government control. Jassa Singh Ahluwalia replied that their meeting place would be the battle ground and the discussion would be carried out by their swords. Beg attacked the Ram Rauni fort at Amritsar and besieged the Sikhs there.[141] Dewan Kaura Mal advised the Governor to lift the siege and prepare the army to protect the state from the Durrani invader, Ahmed Shah Abdali. Kaura Mal had a part of the revenue of Patti area given to the Sikhs for the improvement and management of Harmandir Sahib, Amritsar.[142]

Kaura Mal had to go to Multan to quell a rebellion there. He asked the Sikhs for help and they agreed to join him. After the victory at Multan, Kaura came to pay his respects to the Darbar Sahib, and offered 11,000 rupees and built Gurdwara Bal-Leela; He also spent 3,000,000 rupees to build a Sarover (holy water) at Nankana Sahib, the birthplace of Guru Nanak Dev.[143] In 1752, Kaura Mall was killed in a battle with Ahmed Shah Abdali and state policy towards the Sikhs quickly changed. Mir Mannu, the Governor, started hunting Sikhs again. He arrested many men and women, put them in prison and tortured them. In November 1753[144], when he went to kill the Sikhs hiding in the fields, they showered him with a hail of bullets and Mannu fell from the horse and the animal dragged him to death. The Sikhs immediately proceeded to Lahore, attacked the prison, and got all the prisoners released and led them to safety in the forests.[145]

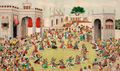

Harmandir Sahib demolished in 1757

In May 1757, the Afghan Durrani general of Ahmad Shah Abdali, Jahan Khan attacked Amritsar with a huge army and the Sikhs because of their small numbers decided to withdraw to the forests. Their fort, Ram Rauni, was demolished,[146] Harmandir Sahib was also demolished, and the army desecrated the Sarovar (Holy water) by filling it with debris and dead animals.[147] Baba Deep Singh made history when he cut through 20,000 Durrani solders and reached Harmandir Sahib, Amritsar.[148][149]

The Khalsa gain territory

Adina Beg did not pay revenues to the government so the Governor dismissed him[150] and appointed a new Faujdar (garrison commander) in his place. The army was sent to arrest him and this prompted Adina Beg to request Sikh help. The Sikhs took advantage of the situation and to weaken the government, they fought against the army. One of the commanders was killed by the Sikhs and the other deserted. Later, the Sikhs attacked Jalandhar[151] and thus became the rulers of all the tracts between Sutlej and Beas rivers, called Doaba.[152] Instead of roaming in the forests now they were ruling the cities.

The Sikhs started bringing more areas under their control and realizing revenue from them. In 1758, joined by the Mahrattas[153], they conquered Lahore and arrested many Afghan soldiers who were responsible for filling the Amrit Sarovar with debris a few months earlier. They were brought to Amritsar and made to clean the Sarovar (holy water).[154][155] After the cleaning of the Sarovar, the soldiers were allowed to go home with a warning that they should not do that again.

Ahmed Shah Abdali came again in October 1759 to loot Delhi. The Sikhs gave him a good fight and killed more than 2,000 of his soldiers. Instead of getting involved with the Sikhs, he made a rapid advance to Delhi. The Khalsa decided to collect revenues from Lahore to prove to the people that the Sikhs were the rulers of the state. The Governor of Lahore closed the gates of the city and did not come out to fight against them. The Sikhs laid siege to the city. After a week, the Governor agreed to pay 30,000 rupees to the Sikhs.

Ahmed Shah Abdali returned from Delhi in March 1761 with lots of gold and more than 2,000 young girls as prisoners who were to be sold to the Afghans in Kabul. When Abdali was crossing the river Beas, the Sikhs swiftly fell upon them. They freed the women prisoners and escorted them back to their homes. The Sikhs took over Lahore in September of 1761, after Abdali returned to Kabul. The Khalsa minted their coins in the name of Guru Nanak Dev. Sikhs, as rulers of the city, received full cooperation from the people. After becoming the Governor of Lahore, Punjab Jassa Singh Ahluwalia was given the title of Sultan-ul-Kaum (King of the Nation).[156]

Wadda Ghalughara (The Great Massacre)

In the winter of 1762, after losing his loot from Delhi to the Sikhs, The Durrani emperor, Ahmad Shah Abdali brought a big, well equipped army to finish the Sikhs forever. Sikhs were near Ludhiana on their way to the forests and dry areas of the south and Abdali moved from Lahore very quickly and caught the Sikhs totally unprepared.[157] They had their women, children and old people with them. As many as 30,000 Sikhs are said to have been murdered by the army.[158][159] Jassa Singh Ahluwalia himself received about two dozen wounds. Fifty chariots were necessary to transport the heads of the victims to Lahore.[160] The Sikhs call this Wadda Ghalughara (The Great Massacre).

Harmandir Sahib blown up in 1762

Ahmad Shah Abdali, fearing Sikh retaliation, sent messages that he was willing to assign some areas to the Sikhs to be ruled by them. Jassa Singh Ahluwalia rejected his offers and told him that Sikhs own the Punjab and they do not recognize his authority at all. Abdali went to Amritsar and destroyed the Harmandir Sahib again by filling it up with gunpowder hoping to eliminate the source of "life" of the Sikhs.[161][162] While Abdali was demolishing the Harminder Sahib a he was hit on the nose with a brick[163]; later in 1772 Abdali died of cancer from the 'gangrenous ulcer' that consumed his nose.[164] Within a few months the Sikhs attacked Sirhind and moved to Amritsar.[165]

Sikhs retake Lahore

In 1764 the Sikhs shot dead Jain Khan[166], Durrani Governor of Sirhind, and the regions around Sirhind were divided among the Sikh Misldars and monies recovered from the treasury were used to rebuild the Harmandir Sahib. Gurdwara Fatehgarh Sahib was built in Sirhind, at the location the two younger sons of Guru Gobind Singh were martyred. The Sikhs started striking Govind Shahi coins[167] and in 1765 they took over Lahore again.[168]

In 1767 when Ahmed Shah Abdali came again he sent messages to the Sikhs for their cooperation. He offered them the governorship of Punjab but was rejected.[169] The Sikhs using repeated Guerrilla attacks took away his caravan of 1,000 camels loaded with fruits from Kabul.[170] The Sikhs were again in control of the areas between Sutlej and Ravi. After Abdali’s departure to Kabul, Sikhs crossed the Sutlej and brought Sirhind and other areas right up to Delhi, the entire Punjab under their control.[171]

Shah Alam II, the Mughal Emperor of Delhi was staying away in Allahabad, ordered his commander Zabita Khan to fight the Sikhs.[172] Zabita made a truce with them instead[173] and then was dismissed from Alam’s service. Zabita Khan then became a Sikh and was given a new name, Dharam Singh.[174]

Qadi Nur Mohammed, who came to Punjab with Ahmad Shah Abdali and was present during many Sikh battles writes about the Sikhs:[175] Template:Cquote

Peace in Amritsar

Ahmad Shah Abdali, fearing the Sikhs, did not follow his normal route through Punjab while he returned to Kabul. Jassa Singh Ahluwalia did not add more areas to his Misl. Instead, whenever any wealth or villages came into the hands of the Sikhs he distributed them among the Jathedars of all the Misls. Ahluwalia passed his last years in Amritsar. With the resources available to him, he repaired all the buildings, improved the management of the Gurdwaras, and provided better civic facilities to the residents of Amritsar. He wanted every Sikh to take Amrit before joining the Dal Khalsa.[176] Ahluwalia died in 1783 and was cremated near Amritsar. There is a city block, Katra Ahluwalia, in Amritsar named after him. This block was assigned to his Misl in honor of his having stayed there and protected the city of Amritsar.

Jassa Singh Ramgarhia

Jassa Singh Ramgarhia played a an active role in Jassa Singh Alhuwalia’s army. He founder of the Ramgarhia Misl[177] and played a major role in the battles of the Khalsa Panth. He suffered about two dozen wounds during the Wadda Ghalughara. Jassa Singh Ramgarhia, was the son of Giani Bhagwan Singh[178] and was born in 1723. They lived in the village of Ichogil, near Lahore. His grandfather took Amrit during the lifetime of Guru Gobind Singh[179], and joined him in many battles; he joined the forces of Banda Singh Bahadur. Ramgarhia was the oldest of five brothers. When Ramgarhia was young he had memorized Nitnem hymns and took Amrit.[180]

Award of an Estate

In 1733, Zakaria Khan, the Governor of Punjab, needed help to protect himself from the Iranian invader, Nader Shah. He offered the Sikhs an estate and a royal robe.[181] The Sikhs in the name of Kapur Singh accepted it. After the battle Zakaria Khan gave five villages to the Sikhs in reward for the bravery of Giani Bhagwan Singh, father of Ramgarhia, who died in the battle. Village Vallah was awarded to Ramgarhia,[182] where Ramgarhia gained the administrative experience required to become a Jathedar (leader) of the Sikhs. During this period of peace with the government, the Sikhs built their fort, Ram Rauni, in Amritsar. Zakaria died in 1745 and Mir Mannu became the Governor of Lahore.

Jassa Singh Honored as Jassa Singh Ramgarhia

Mir Mannu (Mu'in ul-Mulk), the Governor of Lahore, was worried about the increasing power of the Sikhs so he broke the peace. Mir Mannu also ordered Adina Beg, the Faujdar (garrison commander) of the Jalandhar region, to begin killing the Sikhs.[183] Adina Beg was a very smart politician and wanted the Sikhs to remain involved helping them. In order to develop good relations with the Sikhs, he sent secret messages to them who were living in different places. Jassa Singh Ramgarhia responded and agreed to cooperate with the Faujdar and was made a Commander.[184] This position helped him develop good relations with Divan Kaura Mal at Lahore and assign important posts to the Sikhs in the Jalandhar division.

The Governor of Lahore ordered an attack on Ram Rauni to kill the Sikhs staying in that fort. Adina Beg was required to send his army as well and Jassa Singh, being the commander of the Jalandhar forces, had to join the army to kill the Sikhs in the fort.[185] After about four months of siege, Sikhs ran short of food and supplies in the fort. He contacted the Sikhs inside the fort and joined them. Jassa Singh used the offices of Divan Kaura Mal and had the siege lifted.[2] The fort was strengthened and named Ramgarh; Jassa Singh Ramgarhia, having been designated the Jathedar of the fort, became popular as Ramgarhia.

Fighting the tyrannical Government

Mir Mannu intensified his violence and oppression against the Sikhs. There were only 900 Sikhs when he surrounded the Ramgarh fort again.[186] The Sikhs fought their way out bravely through thousands of army soldiers. The army demolished the fort. The hunt for and torture of the Sikhs continued until Mannu died in 1753. Mannu's death left Punjab without any effective Governor. It was again an opportune period for the Sikhs to organize themselves and gain strength. Jassa Singh Ramgarhia rebuilt the fort and took possession of some areas around Amritsar. The Sikhs took upon themselves the task of protecting the people in the villages from the invaders.[187] The money they obtained from the people was called Rakhi (protection charges). The new Governor, Taimur, son of Ahmed Shah Abdali, despised the Sikhs. In 1757, he again forced the Sikhs to vacate the fort and move to their hiding places. The fort was demolished, Harmandir Sahib was blown up, and Amrit Sarovar was filled with debris.[188] The Governor decided to replace Adina Beg. Beg asked the Sikhs for help and they both got a chance to weaken their common enemy. Adina Beg won the battle and became the Governor of Punjab. Sikhs rebuilt their fort Ramgarh and repaired the Harmandir Sahib. Beg was well acquainted with the strength of the Sikhs and he feared they would oust him if he allowed them to grow stronger, so he lead a strong army to demolish the fort.[189] After fighting valiantly, the Sikhs decided to leave the fort. Adina Beg died in 1758.

Ramgarhia Misl Estate

Jassa Singh Ramgarhia occupied the area to the north of Amritsar between the Ravi and the Beas rivers.[190] He also added the Jalandhar region and Kangra hill areas to his estate. He had his capital in Sri Hargobindpur, a town founded by the sixth Guru. The large size of Ramgarhia's territory aroused the jealousy of the other Sikh Misls.[191]

Conflicts between Misls

A conflict between Jai Singh Kanhaiya and Jassa Singh Ramgarhia developed and the Bhangi Misl sardars also developed differences with Jai Singh Kanhaiya. A big battle was fought between Jai Singh, Charat Singh, and Jassa Singh Ahluwalia on one side and Bhangis, Ramgarhias and their associates on the other side. The Bhangi side lost the battle.

Later, Jassa Singh Ahluwalia, one day while hunting, happened to enter Ramgarhia territory where Jassa Singh Ramgarhia's brother arrested him. Ramgarhia apologized for the misbehavior of his brother, and returned Ahluwalia with gifts.[192]

Mutual Misl wars

Due to mutual jealousies, fights continued among the Sikh Sardars. In 1776, the Bhangis changed sides and joined Jai Singh Kanhaiya to defeat Jassa Singh Ramgarhia.[193] His capital at Sri Hargobindpur was taken over and he was followed from village to village,[194] and finally forced to vacate all his territory. He had to cross the river Sutlej and go to Amar Singh, the ruler of Patiala. Maharaja Amar Singh welcomed Ramgarhia and who then occupied the areas of Hansi and Hissar[195] which eventually Ramgarhia handed over to his son, Jodh Singh Ramgarhia.

Maharaja Amar Singh and Ramgarhia took control of the villages on the west and north of Delhi, now forming parts of Haryana and Western U.P. The Sikhs disciplined and brought to justice all the Nawabs who were harassing their non-Muslim population. Jassa Singh Ramgarhia entered Delhi in 1783. Shah Alam II, the Mughal emperor, extended the Sikhs a warm welcome.[196] Ramgarhia left Delhi after receiving gifts from him. Because of the differences arising out of the issue of dividing the Jammu state revenues, long time friends and neighbors Maha Singh, Jathedar of Sukerchakia Misl and Jai Singh, Jathedar of the Kanheya Misl, became enemies. This resulted in a war which changed the course of Sikh history. Maha Singh requested Ramgarhia to help him. In the battle, Jai Singh lost his son, Gurbalchsh Singh, while fighting with Ramgarhias.

The Creation of the United Misl

Jai Singh Kanheya’s widowed daughter-in-law, Sada Kaur, though very young, was a great statesperson. Sada Kaur saw the end of the Khalsa power through such mutual battles but she was able to convince Maha Singh to adopt the path of friendship.[197] For this she offered the hand of her daughter, then only a child, to his son, Ranjit Singh (later the Maharaja of the Punjab), who was then just a boy. The balance of power shifted in favour of this united Misl. This made Ranjit Singh the leader of the most powerful union of the Misls.

When the Afghan invader, Zaman Shah Durrani, came in 1788 the Sikhs, however, were still divided. Ramgarhia and Bhangi Misls were not willing to help Ranjit Singh to fight the invader, so the Afghans took over Lahore and looted it. Ranjit Singh occupied Lahore in 1799[198] but still the Ramgarhias and Bhangis did not accept him as the leader of all the Sikhs. They got the support of their friends and marched to Lahore to challenge Ranjit Singh. When the Bhangi leader died Jassa Singh Ramgarhia returned to his territory.[199] Ramgarhia was eighty years old when he died in 1803. His son, Jodh Singh Ramgarhia, developed good relations with Ranjit Singh and they never fought again.

Sikh Empire

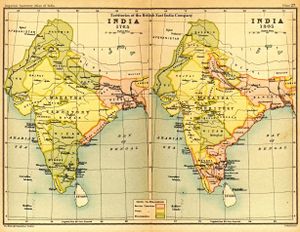

Ranjit Singh was crowned on 12 April 1801 (to coincide with Baisakhi). Sahib Singh Bedi, a descendant of Guru Nanak Dev, conducted the coronation.[200] Gujranwala served as his capital from 1799. In 1802 he shifted his capital to Lahore & Amritsar. Ranjit Singh rose to power in a very short period, from a leader of a single Sikh misl to finally becoming the Maharaja (Emperor) of Punjab.

Ranjit Singh and his Suwarree. 1831.

Maharaja Sher Singh and his council in the Lahore Fort. 1841.

Sher Singh in Lahore. 1845 ca.

Formation

The Sikh Empire (from 1801–1849) was formed on the foundations of the Punjabi Army by Maharaja Ranjit Singh. The Empire extended from Khyber Pass in the west, to Kashmir in the north, to Sindh in the south, and Tibet in the east. The main geographical footprint of the empire was the Punjab. The religious demography of the Sikh Empire was Muslim (80%), Sikh (10%), Hindu (10%),.[201]

The foundations of the Sikh Empire, during the Punjab Army, could be defined as early as 1707, starting from the death of Aurangzeb and the downfall of the Mughal Empire. After fighting off local Mughal remnants and allied Rajput leaders, Afghans, and occasionally hostile Punjabi Muslims who sided with other Muslim forces the fall of the Mughal Empire provided opportunities for the army, known as the Dal Khalsa, to lead expeditions against the Mughals and Afghans. This led to a growth of the army, which was split into different Punjabi Armies and then semi-independent misls. Each of these component armies were known as a misl, each controlling different areas and cities. However, in the period from 1762-1799 Sikh rulers of their misls appeared to be coming into their own. The formal start of the Sikh Empire began with the disbandment of the Punjab Army by the time of Coronation of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1801, creating the one unified political Empire. All the misldars who were affiliated with the Army were nobility with usually long and prestigious family histories in Punjab's history.[202][203]

Punjab Flourishes in Education and Arts

The Sikh rulers were very tolerate of other religions; and arts, painting and writings flourished in Punjab. In Lahore alone there were 18 formal schools for girls besides specialist schools for technical training, languages, mathematics and logic, let alone specialized schools for the three major religions, they being Hinduism, Islam and Sikhism.[204] There were craft schools specializing in miniature painting, sketching, drafting, architecture and calligraphy. There wasn't a mosque, a temple, a dharmsala that had not a school attached to it.[205] All the sciences in Arabic and Sanskrit schools and colleges, as well as Oriental literature, Oriental law, Logic, Philosophy and Medicine were taught to the highest standard. In Lahore, Schools opened from 7am and closed at midday. In no case was a class allowed to exceed 50 pupils.[206]

Punjab Army

The Sikh Fauj-i-Ain (regular army) consisted of roughly 71,000 men and consisted of infantry, cavalry, and artillery units.[207]. Ranjit Singh employed generals and soilders from many countries including Russia, Italy, France, and America.

There was strong collaboration in defense against foreign incursions such as those initiated by Ahmed Shah Abdali and Nader Shah. The city of Amritsar was attacked numerous times. Yet the time is remembered by Sikh historians as the "Heroic Century". This is mainly to describe the rise of Sikhs to political power against large odds. The circumstances were hostile religious environment against Sikhs, a tiny Sikh population compared to other religious and political powers, which were much larger in the region than the Sikhs.

Conquests

In 1834 The Khalsa under Nau Nihal Singh, Hari Singh Nalwa, Jean-Baptiste Ventura, and Claude August Court conquered Peshawar and extended the Sikh Raj upto Jamrud, Afghanistan.[208]

End of Empire

After Maharaja Ranjit Singh's death in 1839, the empire was severely weakened by internal divisions and political mismanagement. This opportunity was used by the British Empire to launch the First Anglo-Sikh War. The Battle of Ferozeshah in 1845 marked many turning points, the British encountered the Punjabi Army, opening with a gun-duel in which the Sikhs "had the better of the British artillery". But as the British made advancements, Europeans in their army were especially targeted, as the Sikhs believed if the army "became demoralised, the backbone of the enemy's position would be broken".[209] The fighting continued throughout the night earning the nickname "night of terrors". The British position "grew graver as the night wore on", and "suffered terrible casualties with every single member of the Governor General's staff either killed or wounded".[210]