Difference between revisions of "Bhai Amrik Singh Ji"

DWNUndaShah (talk | contribs) (→Arrest) |

DWNUndaShah (talk | contribs) (→Arrest) |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

=== Arrest === | === Arrest === | ||

| − | On July 19, 1982 Bhai Amrik Singh was arrested for vehemently pleading the case of the arrested workers causing offense and attention to | + | On July 19, 1982 Bhai Amrik Singh was arrested for vehemently pleading the case of the arrested workers causing offense and attention to Chenna Reddy,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Grewal |first1=J. S. |title=The Sikhs of the Punjab, II.2 |date=October 8, 1998 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=9780521637640 |page=222 |edition=Revised }}</ref> the Governor of Punjab, as well as a possible connection in the attack on Joginder Singh Sandhu, a senior Nirankari leader.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Kaur |first1=Harminder |title=Blue Star Over Amritsar |date=January 1, 1990 |publisher=Ajanta Publications |page=69}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Sharda |first1=Jain |title=Politics of terrorism in India: the case of Punjab |date=1995 |publisher=Deep & Deep Publications |isbn=9788171008070 |page=166}}</ref> |

Sant Jarnail Singh started a ''morcha'' (agitation) on July 19, 1982 for the immediate release of Bhai Amrik Singh and had popular support throughout Punjab, including support from [[Akali Dal]], Darbara Singh, and the farmers of Majha's country side.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Chima |first1=Jugdep |title=The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements |date=August 1, 2008 |publisher=SAGE Publications India |location=New Delhi |isbn=9788132105381 |page=132}}</ref> [[Harcharan Singh Longowal|Harcharan Longowal]], leader of the Akali Dal than announced that his ''morcha'' would also be for the release of Amrik Singh and the 45 original demands presented to [[Indira Gandhi]]. Upon news of Akali Dal's new ''morcha'' for the release of Bhai Amrik Singh Jarnail Singh agreed to discontinue his agitation and join the Akali Dal's planned [[Khalistan_movement#Dharam_Yudh_Morcha|Dharm Yudh Morcha]] which began in August 4, 1982. | Sant Jarnail Singh started a ''morcha'' (agitation) on July 19, 1982 for the immediate release of Bhai Amrik Singh and had popular support throughout Punjab, including support from [[Akali Dal]], Darbara Singh, and the farmers of Majha's country side.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Chima |first1=Jugdep |title=The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements |date=August 1, 2008 |publisher=SAGE Publications India |location=New Delhi |isbn=9788132105381 |page=132}}</ref> [[Harcharan Singh Longowal|Harcharan Longowal]], leader of the Akali Dal than announced that his ''morcha'' would also be for the release of Amrik Singh and the 45 original demands presented to [[Indira Gandhi]]. Upon news of Akali Dal's new ''morcha'' for the release of Bhai Amrik Singh Jarnail Singh agreed to discontinue his agitation and join the Akali Dal's planned [[Khalistan_movement#Dharam_Yudh_Morcha|Dharm Yudh Morcha]] which began in August 4, 1982. | ||

Revision as of 13:52, 6 November 2019

Bhai Amreek Singh ji | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1948 |

| Died | June 6, 1984. |

| Office | President of AISSF |

| Predecessor | Hari Singh[1] |

| Successor | Manjit Singh[2] |

| Spouse(s) | Bibi Harmeet Kaur |

| Children | Satwant Kaur, Paramjit Kaur, and Tarlochan Singh |

| Parent(s) |

|

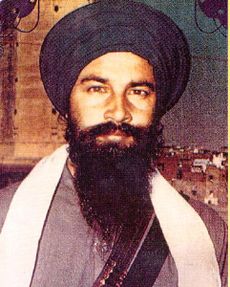

Bhai Amrik Singh ji (1948 – June 6, 1984) was the President of the Sikh Students Federation and was killed in the army operation in Golden Temple, Amritsar, on June 6, 1984.[3]

Bhai Amrik Singh was the son of Giani Kartar Singh Bhindranwale, the 13th leader of the Damdami Taksal.[4] He was well versed in Gurbani and Sikh literature, and devoted much of his life to Sikh progressive activities. He had passed his Masters in Punjabi from Khalsa College in Amritsar after which he began research work on his Ph.D. thesis.

Bhai Amrik Singh was a prominent leader of the orthodox Sikh faction along with Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. He contested the 1979 Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) election, backed by Bhindranwale, but lost to Jiwan Singh Umranangal.[5]

On 26 April 1982, he led a campaign to get Amritsar the status of a "holy city". During the agitation, he was arrested on 19 July 1982 along with other members of the Damdami Taksal. Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale began the Dharam Yudh Morcha to implement the Anandpur Resolution which primarily requested more autonomy for the Punjabi's, arguing that they were being oppressed and treated unfairly by the Indian government. As part of the Morcha, he also demanded freedom for Bhai Amrik Singh[6] and other prominent Sikhs.

Contents

- 1 Biography

- 1.1 Birth and family

- 1.2 Education

- 1.3 Work with AISSF

- 1.4 Arrest

- 2 References

Biography

Birth and family

Bhai Amrik Singh was born in 1948 as the son of Giani Kartar Singh Bhindranwale, the 13th leader of the Damdami Taksal.[7] Manjit Singh was his younger brother.[8]

Education

Bhai Amrik Singh studied at Khalsa College[9] and received his MA and was on his way to completing his PhD before pursuing promotion of Sikh teachings.

Work with AISSF

Bhai Amrik Singh was made president of the AISSF on July 2 1978 at large AISSF meeting held at Tagore Theatre, Chandigarh.[10]

Building Gurdwara Shaheed Ganj in honor of the Sikhs massacred in 1978

Bhai Amrik Singh contributed significantly to opposing the Nirankaris and to the building of the Gurdwara Shaheed Ganj, in B-Block Amritsar, at the spot where the 13 Sikh protesters were murdered[11] by the Nirankaris. When no other organization came forth and the government refused to sell the land to Amrik Singh and the AISSF the AISSF Sikhs began building the Gurdwara wall at night so they could claim the land by force.[12] Sikh youth would spend the entire night building the wall and it would be knocked down by the police the next day. A stand off between the police and the AISSF began and the police threatened they would shoot anyone on site, they were met with resolve from Amrik Singh who said they would do anything to raise the memorial for the martyred Sikhs. Eventually the police acceded to the demands of the Sikhs and the Gurdwara remains there today.

Running for SPGC Elections

In the General House Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) elections of 1979, the first in 13 years,[13] Amrik Singh ran and lost to Jiwan Umramangal.[14] Amrik Singh was in the Dal Khalsa and Bhindranwale's group (who fielded about 40 candidates) running against the Akali Dal and ran for the SGPC Beas constituency.[15] Notably one of The Dal Khalsa aim included establishing a independent Sikh State. Some elements of the Congress party supported and backed Dal Khalsa's and Bhindranwale's group so they could undermine the Akalis.[16]

Strikes and agitations

The AISSF held a strike on October 25 1980 and another on November 14, 1980 to protest against the high bus fare increase and some other issues in such districts as Amritsar, Gurdaspur, Jalandhar, Patiala, Ludhiana with trains not being able to operate then. This resulted in student-police clashes at numerous places causing the police to open fire at Dasuya and Jhabhal.[17] On the November 14, 1980 strike against the bus fare increase organized by the AISSF there was jammed traffic in the province. The residents of the province provided full support for the Sikh students.[18] Following these agitations all political parties joined the struggle against the increased bus fares. Some reports are there of police stations being attacked.[19]

The AISSF held numerous agitations, strikes, street riots against various causes and politicians.[20] During the time of the bus fare agitations the AISSF also held numerous demonstrations against various political leaders including the chief minister of Punjab, Darbara Singh. Some notable agitations including Sikh students besieging various Punjab ministers and lock themselves inside their offices or residences during early December of 1980. The students responsible were arrested and tortured and more subsequent agitations was launched for the release of these students with these agitations were so forceful that the police release the students within a couple of days.[21]

The success of the AISSF, which this time numbered to a membership of 300,000 members,[22] at one point compelled the non-government political parties to join in and hold a demonstration in front of the state secretariat at Chandigarh from making a speech, on January 1981. Thousands of AISSF volunteers joined the demonstration with more than a thousand being arrested and eventually police throwing tear-gas and also lathi and cane-charged them however the AISSF were successful in delaying the Punjab governor from making a speech making the government invite all the political parties for a dialogue.

Anti Tobacco march

This issue of banning tobacco in and other improvements to Amritsar also put leeway to get the Sikh issues to mainstream politics.[23] In May of 1981 The AISSF alongside Dal Khalsa put forth to pass the bill of banning tobacco in the city of Amritsar, tobacco is strictly forbidden in Sikhism, this bill was originally introduced in 1977 by the Akali Dal for the 400 years founding of Amritsar celebrations. The AISSF gave an ultimatum to the Punjab government to ban tobacco in the city by March 30th or there would be an agitation.[24] The Government of Punjab seemed to agree with the issue but they said that technically passing such a ban would be unconstitutional and therefore could not. Meanwhile AISSF members forcibly started preventing merchants from selling tobacco[25] and to add to the heat Harchand Longowal also publicly expressed his support for the ban.[26]

Opposition's pro tobacco march

On May 29 1981 thousands of Hindus marched in Amritsar to protest against the AISSF ban for tobacco demand.[27] They carried sticks with lit cigarettes through the Amritsar bazaar, beating up Sikhs along the way and yelling provocative slogans.[28]

Bhindranwale's march

In response to the pro tobacco march, on May 31th 1981, the AISSF, Damdami Taksal, Dal Khalsa joined together led by Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and with over 20,000[29] supporters put out a procession. No major Akali leader participated in the march. The march went a route of about two and a half kilometres.[30] Following the march there were eruptions of Hindu-Sikh clashes in Amritsar with the government then initating new laws banning non-religious processions from taking place. These events died down once the government agreed to form a committee to discuss 'holy-city' status for Amritsar.

Outcome

Holy-city status was not given to Amritsar however on February 27 1983 the Prime Minister passed a law making meat, alcohol and tobacco sale prohibited in the areas around the Harimander Sahib and the Hindu Durgiana temple in Amritsar.[31] On September 10 2016 Aam Aadmi Party leader Arvind Kejriwal promised 'holy-city' status to Amritsar as well as Anandpur Sahib[32] on his visit to the city. He declared liquor, tobacco, cigarette and meat will be completely banned in these cities, it is notable the sales of such items are currently rampant in the city.

Bhindranwale's arrest

Bhai Amrik Singh played a major role in movements for the release of Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. On September 13 1981 the government issued warrents for Sant Jarnail Singh in the case of the murder of news reporter Lala Jagat Narian.[33] On September 14th the police laid saige to village Chando Kalan where Sant Jarnail Singh was staying, police were later charged with trying to kill him there and then in a fake encounter,[34][35] however the police were not able to capture him. In retaliation they set fire to two large buses belonging to the Damdami Taksal.[36] The buses contained saroops (texts) of Guru Granth Sahib,[37] several other religious books and cassette recordings, and burning them in such a manner was considered a massive sacrilege in Sikhism. The police also opened fire killing scores of residents of village[38] while no Sikh attacked back.

For this sacrilege,[39] the Sikh students observed September 16 as a protest day and took out many protest marches throughout several cities and towns of Punjab. At Amritsar, the police ran amuck and using canes and tear-gas attacked not only the peaceful protestors but the students and professors of Khalsa College.[40] The police entered the hostels ransacking the rooms of students and taking away several belongings.

September 20th firing

On September 20th 1981 when Sant Jarnail Singh offered himself for arrest[41] and argued that the government attacked him and opened fire on his people without a chance to go for arrest in the legal way a large group of over 75,000 Sikhs[42] had reached Metha Chowk with Bhai Amrik Singh was in charge of this ceremony and almost all major leaders of all notable Sikh organizations reached there. Sant Jarnail Singh who was dressed in saffron clothes, clothes associated with martyrdom,[43] urged the the Sikhs to maintain peace at all costs.[44] After the arrest of Sant Jarnail Singh, the police and paramilitary forces opened indiscriminate fire on the Sikhs returning to their homes killing several Sikhs and wounding several hundreds.[45]

AISSF bombings

Having seen the the Akali Dal Civil Disobedience movement for the release of Bhindranwale make little effect on the government the AISSF began making several so called 'harmless' explosions at several places in Punjab[46] and threatened that if Sant Jamail Singh was not released immediately, the entire Punjab would become a warzone. The government began arresting several hundred Sikh students in association of the explosions, many of which were entirely false charges.[47] During this phase planes where also hijacked for the release of Sant Jarnail Singh.[48][49]

Bhindranwale's release

Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale was released on bail on October 15th 1981 as there was no evidence against him.[50]

Aspiration for Khalsa College students

For the discrimination and abuse the professors and the students faced at Khalsa College by the police Bhai Amrik Singh wanted the Akali party to follow through and not talk to the government until the government made a significant effort and put out a judicial inquiry into the events of what happened on Khalsa College on September 16th 1981, as well as hold an account into the massacre of the Sikhs at Madhuban, Haryana as well as hold an inquiry for the burning of the vehicles at Metha Chowk. After some hesitation the Akali Dal eventually joined this boycott action.[51]

On November 24th 1981 the AISSF held a massive strike throughout the schools, colleges, and all educational institutes of Punjab remained closed, in such districts ranging from Amritsar, Gurdaspur, Jalandhar, Patiala, Bathinda, Kapurthala, Sangrur. AISSF demanded a judicial inquiry into the police excesses at Khalsa College Amritsar before the schools would reopen as well as release of all the Sikh students.

On December 16th 1981 at Khalsa College Amritsar in a massive convention was held at at Khalsa College for Sikh students where Sant Jarnail Singh gave out honorary siropai (garlands) to all the professors, students, and the other people, who were attacked by police on the occasion of the protest rally held against Sant Jarnail Singh arrest.[52] Several hundreds of students are said to have got baptized into the Khalsa order on this day.

Arrest

On July 19, 1982 Bhai Amrik Singh was arrested for vehemently pleading the case of the arrested workers causing offense and attention to Chenna Reddy,[53] the Governor of Punjab, as well as a possible connection in the attack on Joginder Singh Sandhu, a senior Nirankari leader.[54][55]

Sant Jarnail Singh started a morcha (agitation) on July 19, 1982 for the immediate release of Bhai Amrik Singh and had popular support throughout Punjab, including support from Akali Dal, Darbara Singh, and the farmers of Majha's country side.[56] Harcharan Longowal, leader of the Akali Dal than announced that his morcha would also be for the release of Amrik Singh and the 45 original demands presented to Indira Gandhi. Upon news of Akali Dal's new morcha for the release of Bhai Amrik Singh Jarnail Singh agreed to discontinue his agitation and join the Akali Dal's planned Dharm Yudh Morcha which began in August 4, 1982.

Bhai Amrik Singh was released in the summer of 1983 and subsequently honoured at the Akal Takht with flowered garland saropas (robes of honour).[57]

References

- ↑ Singh, Gurrattanpal (1979). The Illustrated History of the Sikhs, 1947-78: Containing Chapters on PEPSU, AISSF, Evolution of the Demand for Sikh Homeland, and the Princess Bamba Collection. Chandigargh. p. 65.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Chima, Jugdep (August 1, 2008). The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India. p. 132. ISBN 9788132105381.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Khanna, Hans (1987). Terrorism in Punjab: Cause and Cure. Chandigarh: Panchnad Research Institute.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Akbar, M. J. (January 1, 1996). India: The Siege Within : Challenges to a Nation's Unity. UBSPD. p. 183. ISBN 9788174760760.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Crenshaw, Martha (November 1, 2010). Terrorism in Context. Penn State Press. p. 383 "Sant Bhindranwale, leading a major revivalist movement by this point, followed in July with a seperate movement for the release from jail of All India Sikh Students Federation (AISSF) leader Amrik Singh.". ISBN 9780271044422.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Akbar, M. J. (January 1, 1996). India: The Siege Within : Challenges to a Nation's Unity. UBSPD. p. 183. ISBN 9788174760760.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Chima, Jugdep (August 1, 2008). The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India. p. 132. ISBN 9788132105381.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Kumar, Ram (April 1, 1997). The Sikh unrest and the Indian state: politics, personalities, and historical retrospective. Ajanta. p. 22. ISBN 9788120204539.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Singh, Gurrattanpal (1979). The Illustrated History of the Sikhs, 1947-78: Containing Chapters on PEPSU, AISSF, Evolution of the Demand for Sikh Homeland, and the Princess Bamba Collection. Chandigargh. p. 65.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Sarna, Dr. Jasbir (2012). Some Precious Pages Of The Sikh History. Unistar. p. 136. ISBN 978-93-5017-896-6.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Chima, Jugdep (2010). The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9789351509530.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Appleb, R. Scott; Marty, Martin E. (1996). Fundamentalisms and the State: Remaking Polities, Economies, and Militance. University of Chicago Press. p. 262. ISBN 9780226508849.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Akbar, M. J. (1996). India: The Siege Within : Challenges to a Nation's Unity. UBSPD. p. 183. ISBN 9788174760760.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Grewal, J. S. (1998). The Sikhs of the Punjab, II.2 (Revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 217. ISBN 9780521637640.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Singh, Dalip (1981). Dynamics of Punjab Politics. Macmillan. p. 137.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Sarna, Dr. Jasbir (2012). Some Precious Pages Of The Sikh History. Unistar. p. 135. ISBN 978-93-5017-896-6.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Gandhi, Indira (1985). Selected Thoughts of Indira Gandhi: A Book of Quotes. Mittal Publications. p. 10.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Kiss, Peter A. (2014). Winning Wars amongst the People: Case Studies in Asymmetric Conflict. Potomac Books, Inc.,. p. 89. ISBN 9781612347004.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Sarna, Dr. Jasbir (2012). Some Precious Pages Of The Sikh History. Unistar. p. 135. ISBN 978-93-5017-896-6.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Kiss, Peter A. (2014). Winning Wars amongst the People: Case Studies in Asymmetric Conflict. Potomac Books, Inc.,. p. 89. ISBN 9781612347004.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Chima, Jugdep (August 1, 2008). The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9788132105381.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Kumar, Raj. Punjab crisis: Role of Rightist and Leftist Parties. Dev Publications. p. 65. ISBN 9788187577058.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Chima, Jugdep (August 1, 2008). The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9788132105381.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Adiraju, Venkateswar (1991). Sikhs and India: Identity Crisis. Sri Satya Publications. p. 177.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Jeffrey, Robin. What’s Happening to India?: Punjab, Ethnic Conflict, and the Test for Federalism (Second ed.). p. 144.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Kaur, Harminder (1990). Blue Star Over Amritsar. Ajanta Publications. p. 61. ISBN 9788120202573.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Jeffrey, Robin. What’s Happening to India?: Punjab, Ethnic Conflict, and the Test for Federalism (Second ed.). p. 144.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Kamath, M.V.; Gupta, Shekhar; Kirpekar,, Subhash; Sethi,, Sunil; Singh, Tavleen; Singh,, Khushwant; Aurora, Jagjit; Kaur, Amarjit (2012). The Punjab Story. Roli Books Private Limited. ISBN 9788174369123.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Sohan, Sohata; Dharam, Sohata. Sikh Struggle for Autonomy, 1940-1992. Guru Nanak Study Centre,. p. 130. ISBN 9788190029506.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Dhillon, Kirpal (2006). Identity and Survival: Sikh Militancy in India 1978-1993. Penguin UK. ISBN 9789385890383.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Darshi, A. R. (2004). The Gallant Defender. ISBN 9788176014687.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Jalandhary, Surajit (198). Bhindranwale Sant. Punjab Pocket Books.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Chima, Jugdep (2010). The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9789351509530.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Basu, Jyoti (1998). Documents of the Communist Movement in India: 1980-1981, Volume 19. National Book Agency. p. 377. ISBN 9788176260251.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Dhillon, Gurdarshan (1992). India Commits Suicide. Singh & Singh Publishers. p. 1992.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Dhillon, Gurdarshan (1996). Truth about Punjab: SGPC White Paper. Amritsar: Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee. p. 172.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Danewalia,, Bhagwan (1997). Police and politics in twentieth century Punjab. Ajanta. p. 408.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Chima, Jugdep (2010). The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9789351509530.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Gaur, I. D. (2008). Martyr as Bridegroom (First ed.). New Delhi: Anthem Press. p. 116. ISBN 9781843313489.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Dhillon, Gurdarshan (1992). India Commits Suicide. Singh & Singh Publishers. p. 150.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Kaur,, Rajinder (1992). Sikh identity and national integration. Intellectual Pub. House. p. 75.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Chima, Jugdep (August 1, 2008). The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India. p. 64. ISBN 9788132105381.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Sarna, Dr. Jasbir (2012). Some Precious Pages Of The Sikh History. Unistar. p. 143. ISBN 978-93-5017-896-6.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Kumar, Ram; Sieberer, Georg (1991). The Sikh struggle: Origin, Evolution, and Present Phase. Chanakya Publications. p. 258.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Rapoport, David (2001). Inside Terrorist Organizations. Southgate,London: Routledge. p. 188.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Chum, B. K. (2013). Behind Closed Doors: Politics of Punjab, Haryana and the Emergency (Revised ed.). Hay House, Inc,. ISBN 9789381398623.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Sarna, Dr. Jasbir (2012). Some Precious Pages Of The Sikh History. Unistar. p. 142. ISBN 978-93-5017-896-6.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Sarna, Dr. Jasbir (2012). Some Precious Pages Of The Sikh History. Unistar. p. 143. ISBN 978-93-5017-896-6.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Grewal, J. S. (October 8, 1998). The Sikhs of the Punjab, II.2 (Revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 222. ISBN 9780521637640.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Kaur, Harminder (January 1, 1990). Blue Star Over Amritsar. Ajanta Publications. p. 69.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Sharda, Jain (1995). Politics of terrorism in India: the case of Punjab. Deep & Deep Publications. p. 166. ISBN 9788171008070.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Chima, Jugdep (August 1, 2008). The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India. p. 132. ISBN 9788132105381.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>

- ↑ Rastogi, P. N. (1986). Ethnic Tensions in Indian Society: Explanation, Prediction, Monitoring, and Control. Delhi: Mittal Publications. p. 138.<templatestyles src="Module:Citation/CS1/styles.css"></templatestyles>